New Deregulation Advocacy Paper Swings and Misses

It’s been a tough run for supporters of retail utility deregulation. Few states in the last 15 years have shown enthusiasm for adopting the model, and the handful of states that did restructure their utilities in the 1990s and early-2000s have been retreating from it in various ways. It’s not hard to see why. When it comes to electricity, customers care most about reliability, affordability, and consumer protection. Unfortunately, retail deregulation has failed to deliver in these areas.

Against that backdrop, retail deregulation supporters have released a new paper that purports to show the benefits of deregulation. But it is a swing—and a miss. The paper, titled, “At the Crossroads: Improving Customer Choice for Products in the U.S. Electricity Sector,” but it might have more accurately been named, “When it Comes to Utility Deregulation, Don’t’ Believe Your Lying Eyes.”

Much of it is a re-hash of the theoretical case for deregulation, but what is most revealing is what the paper does not address. It sweeps under the rug the obvious problems that all but the most ardent deregulation supporters plainly see.

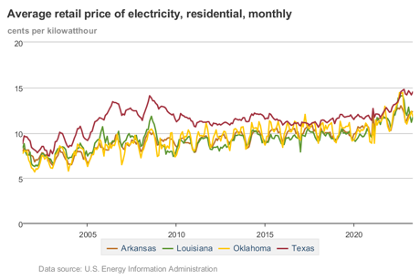

As an initial matter, let’s look at residential retail rates. The paper references several academic studies, and it acknowledges the difficulty in crafting apples-to-apples comparisons across states with various regulatory regimes and resource mixes. That is all well and good – but sometimes a little common sense goes a long way. Just look at average residential electricity rates in Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. Their rates all started in a similar place 20 years ago, and all are contiguous states with a similar resource base. Yet Texas – which is the only one of those states that is overwhelmingly deregulated – has consistently had the highest residential rates for the past two decades. If retail choice worked, wouldn’t there be some point at which the price benefits for customers would be clear?

Another concern, is that the study ignores compelling evidence that retail suppliers charge residential customers much more for power. The study does this by combining residential, commercial and industrial rates into a single number. For an example of why this is misleading, in Massachusetts, the Attorney General recently released a study showing “that in the last six years, individual residential customers who received their electric supply from competitive suppliers paid $525 million more on their electric bills than they would have paid if they stayed with their utility companies.” The study intentionally gives the false impression that residential customers in the Bay State are paying less for power, when, in fact, the opposite is true.

When it comes to reliability, the paper again buries the obvious. Why is it, for example, that the most noteworthy reliability challenges keep happening in states – like Texas and California – that have enacted forms of retail choice and/or utility unbundling? It’s a good question, but not one you’ll hear broached in the paper. It goes so far as to declare that the Texas Winter Storm Uri experience validates the retail competition model. That’s quite a statement considering that experts like Ed Hirs have exhaustively explained why the Texas market structure is actually a root cause of the reliability crises.

Or take for another example, consumer protection. The paper acknowledges a few bad apples engaging in deceptive sales and marketing, but soft pedals the extent of the problem and suggests it can be fixed with better rules and customer education. Yet as Attorneys General and consumer advocates have noted, when it comes to the residential electricity market, consumer protection problems seem to be the feature of electricity retail choice programs, not a bug. In Massachusetts alone, the Attorney General estimates tens of millions of dollars in net consumers losses each year thanks to the residential retail choice scheme.

The challenge for fans of deregulation is that their preferred policies are no longer theoretical prescriptions. We are now dealing with known, comparative policy choices, rather than a referendum on whether traditional utility regulation is perfect. Contrary to the paper’s assertion that we are still learning in “these early years of retail competition,” in truth, we have close to a quarter-century’s worth of experimentation. In that time, the policy hasn’t resulted in lower costs to consumers. It hasn’t provided a more reliable source of power. And it has been a wellspring of consumer protection pitfalls. That’s a track record of failure that will be hard for deregulation’s supporters to overcome when pitching their ideas to lawmakers.